R = Roman, LR = Late Roman, EMA = Early Middle Ages, Ma = 11th c. onwardsThis chapter provides an overview of the archaeobotanical materials used for this research project. Literature review provided an historical overview of the discipline, while this chapter discusses the goals, types, and preservation modes of the remains. In addition to discussing general aspects of the discipline, this chapter also provides a more detailed examination of the specific data available for this research project, which have been stored in the database. The database storing procedures are described in Chapter 5.

The objective of archaeobotany is to recover, identify, and document plant remains from archaeological sites to reconstruct past vegetation dynamics, human-environment interactions, and food production and consumption patterns. Archaeobotany can also be referred to as “palaeoethnobotany”, a term especially prevalent in North America. Although the word “palaeoethnobotany” places a stronger stress on the human and ethnic interaction with plants (Hastorf and Popper, 1988), the two words are used mostly interchangeably (Hastorf, 1999) as European archaeobotanists share the same objectives. It is important to emphasise that the term “palaeobotany” is not a valid synonym for archaeobotany, as it refers to the study of past evolution and adaptations of plants, and this discipline is not concerned with human-environment interactions (Fuller and Lucas, 2014). In Classical archaeology, some of the archaeobotanical research questions can also be inferred from historical literature. This is problematic, as the evidence often contradicts what is said in texts; Pearsall (2015, p. 27) remarks how the discipline works using an archaeological approach, not an historical one. Furthermore, the domain of archaeology stretches far beyond the chronological range of textual history. In the archaeological record, four types of botanical remains can be identified—macroremains, pollen grains, phytoliths (inorganic elements found in leaves, stems, and other parts of plants), and starches (formed by amylose or amylopectin polymer aggregates) (Pearsall, 2015). Most archaeobotanical studies in Italy deal with macroremains and pollen, although this research will only focus on the former.

Macroremains such as seeds, nutshells, fruit pips, and charcoal (wood preserved after carbonisation) are visible to the naked eye (> 0.25 mm). It is possible to recover macrofossils—in situ, by screening using sieves, and by flotation. In situ collection is possibly the most problematic, as it relies on the experience of the excavator and favours larger finds. In addition, light conditions and the colour of the soil might influence the ability to visualise seeds and charcoal remains. A solution to this problem is to use screening techniques, and choosing an appropriate mesh size can limit the bias for underrepresented taxa (e.g. particularly small seeds). Often, sieves of different mesh sizes are used at the same time for the purpose of eliminating as much soil as possible from the soil sample. In addition to dry screening, archaeologists also use wet screening. Wet screening refers to the practice of pouring water onto the sieve. It differs from wet sieving, which requires the submersion of seeds in a bucket with water that is gently agitated. In any case, adding water to the sieve can be counter-productive, as wetting might destroy the seeds if they are charred (White and Shelton, 2014). One of the most common types of recovery is by flotation, which encompasses several techniques, each based on the principle that water is denser than charred material. Flotation can be either manual or machine-assisted. The former refers to wet sieving, where seeds are submerged in water and the ones that float are recovered using a mesh. Tools and machines have been also developed for flotation, including the hand-pump (which does not require electricity) and other machine-assisted tools (see Figure 3.1) that use water pressure and aeration to separate the seeds from soil. Flotation also allows the recovery of other small-sized archaeological material, including fish and bird bones, and mollusca (Jarman et al., 1972; Turney et al., 2005, p. 125; Williams, 1973). After separating the seeds from the soil, seeds can be identified and quantified. For the identification, researchers use fossil reference collections and photographs (Turney et al., 2005).

A sample is a smaller subset of elements from a population. In statistics, a population is the entire set of elements which we can draw inferences from. Often, it is not possible to know how large is the population, which is then called universe. Whether consciously or not, archaeology has always dealt with sampling. Much of the archaeological record has been lost or destroyed in time, and what we are able to study is a smaller portion of what once was present (Drennan, 2010, p. 80). If we consider the entire statistical population what is currently available to the archaeologist, it would be possible to sample for instance each bucket of soil excavated and count the total number of seeds found. This will certainly provide the most accurate information, although it is almost never possible in real life situations. Common constraints are time, funding, number of excavators, etc. It is then up to the archaeologist to decide how to collect samples, which will be biased by definition since they will not reflect reality. Why bother with sampling then? Archaeobotanical macroremains can be smaller than 1 mm and sampling can provide more information than collecting seeds with the naked eye (i.e. no sampling) (Orton, 2000, p. 148). Moreover, an effective and robust sampling strategy can limit bias as far as possible and try to return meaningful samples. Depending on the context, resources and individual decisions, several possibilities are available—interval sampling, probabilistic sampling, judgemental sampling, total sampling, or no sampling at all (Jones, 1991). The first, interval (or systematic) sampling, consists in sampling at regular intervals. The intervals can be defined in space (samples evenly spaced out in a grid), in time (sampling every tot. minutes or every \(n\)-th bucket), or in the laboratory using a riffle box (a machine designed to divide samples). One drawback of this method is that the regularity in sampling might correspond to a regular pattern in the data, which may bias the results. Probabilistic sampling is a method often advocated for, but rarely used. This type of sample has the advantage of allowing the researcher to draw statistical inferences on the data collected, for instance to calculate the margin of error and confidence intervals. The simplest form of probabilistic sampling is random sampling, for example randomly choosing to sample a square from a grid or a bucket from a series of buckets. Another approach to random sampling is cluster sampling, which requires a prior division of the sampling population into clusters (e.g. by context, area, etc.) and then randomly select some of these clusters during excavation (Orton, 2000). One of the problems that may arise from random and cluster sampling approaches is that of spatial autocorrelation. As Waldo Tobler (1970) puts it:

“The first law of geography: Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things.”

Other forms of sampling include judgemental sampling, a feature based approach and total (or blanket) sampling which consists in taking a certain amount of soil from each excavated context. Both methods will be discussed more in detail below. Finally, an excavation can have no sampling at all. Most of the archaeobotanical samples with macroremains recorded in the database were collected using different types of visual sampling, not always made explicit by the authors. Visual sampling occurs when archaeologists can visually see or expect (i.e. judgemental sampling) macroremains in the feature they are excavating. Common features from which samples are usually collected include—pits, hearths, filled anforae, etc. But “how can one argue that the contents of a pit reflect activities involving food specific to that context, if one has not examined samples from floor deposits into which the pit was dug, or the deposits overlying it?” (Pearsall, 2015, p. 75). Lennstrom and Hastorf (1995) lament “feature biases” in many archaeological excavations, as paleobotanists are often called after archaeologists have already recovered materials from specific site features. The authors call for a general misconception in the goal of archaeobotany—to collect as many macroremains as possible. This strategy is, in fact, not very informative about the relationships between plant remains and stratigraphic units, and the general deposition patterns in the site. For instance, Jones et al. (1986) were able to reconstruct the functions of structures and the methods of crop storage at Assiros, northern Greece, through a thorough extensive sampling. Pearsall (2015, p. 74) recommends a “blanket sampling” strategy, which consists in collecting samples for flotation from each stratigraphical unit. The advantages of blanket sampling are manifold:

If in theory sampling from strategical features (e.g. hearths) maximizes the chances of recovering more macrobotanical remains, in practice this is not always the case. For instance, if a hearth was used on a regular basis, it could possibly have been cleaned of ashes frequently, and the excavator might have more luck sampling around it.

Including the collection of samples from each layer in the excavation leads an uniform and standardised procedure, reducing the variation across samples.

Blanket sampling allows an easier reconstruction of deposition patterns and of stratigraphic units relations as stated above. For instance, one can analyse differences in macroremains densities across samples.

In addition to choosing the most efficient sampling strategy, sample size is also a problem that has been discussed in archaeobotany. The sample size, often indicated in litres in archaeological reports, can be constant or variable depending on the context. The size can have important repercussions on the richness of the sample, a topic that will be dealt with more extensively in the chapter discussing the methods used in this thesis. In short, a particularly small sample size can affect the number of species found. In particular, rare species may be either not represented or under-represented (Pearsall, 2015, p. 160). While archaeobotanists have advocated for more specific sampling strategies for over 40 years, very few of the Italian excavations in this dataset applied blanket or probabilistic sampling, and collecting samples from features is still the most common practice.

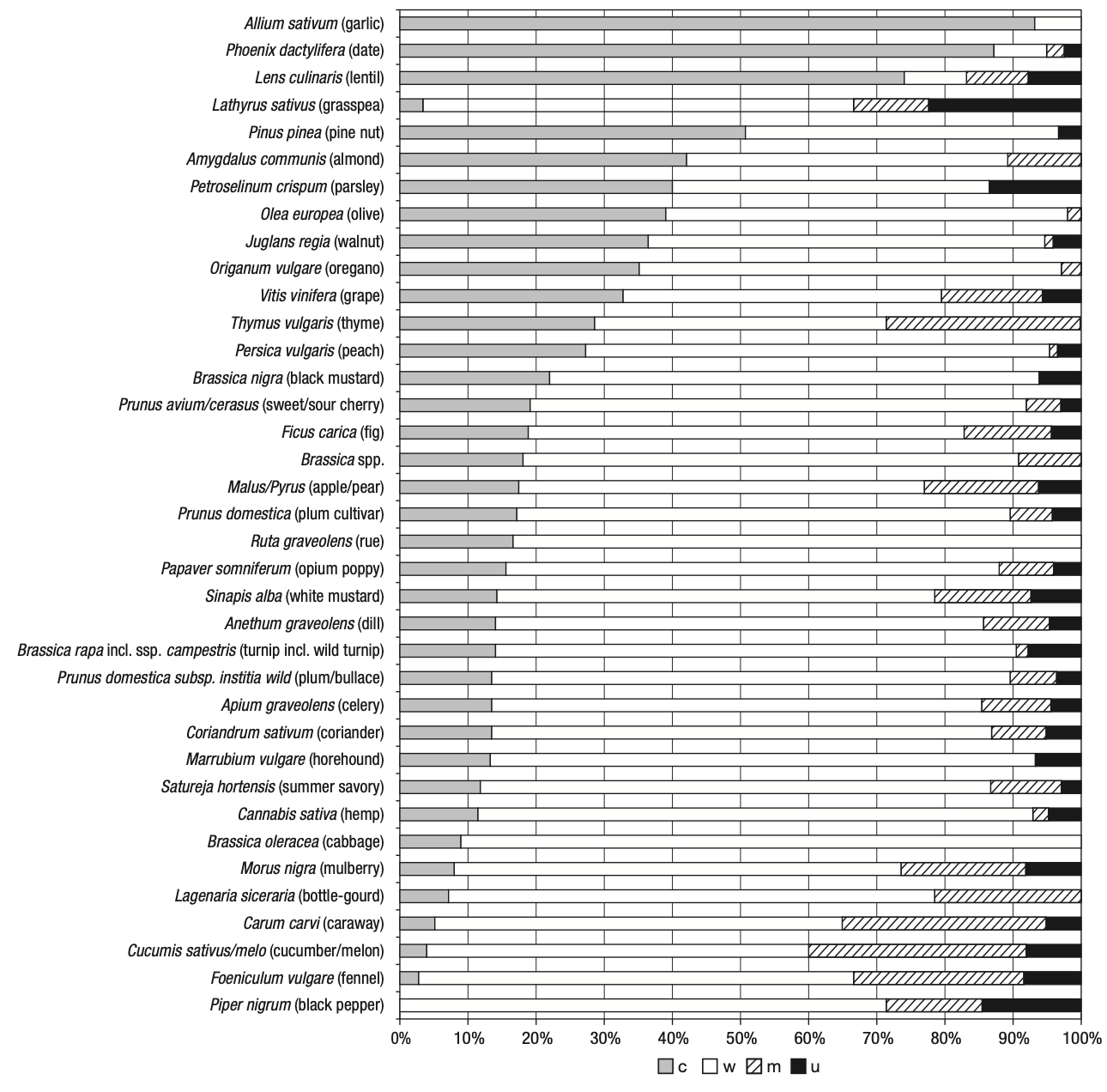

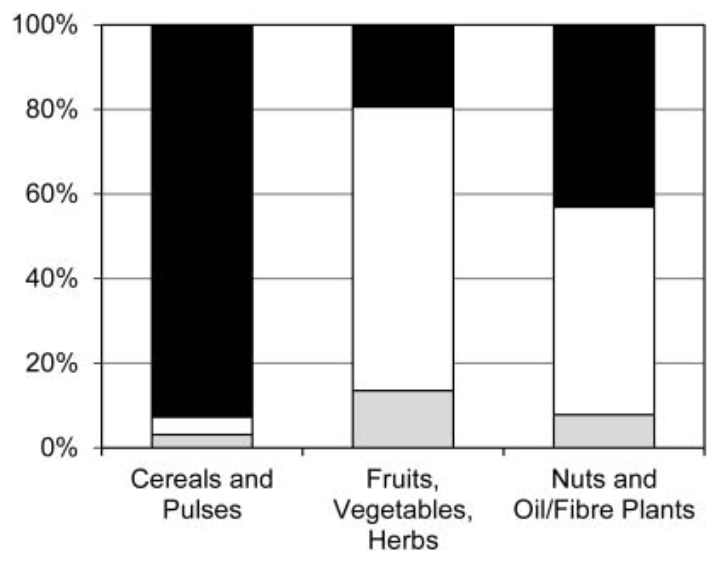

There are several ways in which seeds can be preserved, among them charring (or carbonisation), mineralisation, waterlogging, desiccation, metal oxide preservation and as imprints in ceramics (Fuller and Lucas, 2014). This section will focus only on grain preservation, excluding wood remains, as anthracological data (charred wood) has not been recorded on the database. The mode of preservation has a strong effect on the species of plants that can be found in the archaeological level. Cereals and nuts have higher chances of being preserved by charring, while fruit pips, herbs and spices are most common in waterlogged sediments. Nuts, fibrous and oil-rich plants are also equally preserved under water. Desiccation greatly preserves several parts of a plant, although it occurs very rarely (Veen, 2018, p. 71). These factors influence the representation of plants in the archaeological context, and one must be aware that the most identified taxa may represent the plants that had the best chance of being preserved. The most represented taxa therefore do not necessarily coincide with the most numerous or used plants at the site being investigated (Pearsall, 2015, p. 42). Figure 3.2 and Figure 3.3 show how different preservation methods affect the representation of a taxon.

c= charred, m = mineralised, w = waterlogged, u = unknown]. Image after Livarda (2018).

A final comment must be made on the state of preservation of botanical macrofossils. Regardless of how the seeds have been preserved from deposition to the time of excavation, the state of preservation of individual seeds may also be affected by mechanical actions such as fragmentation or erosion. Indeed, it is not uncommon for an archaeologist to find seeds that are only partially intact.

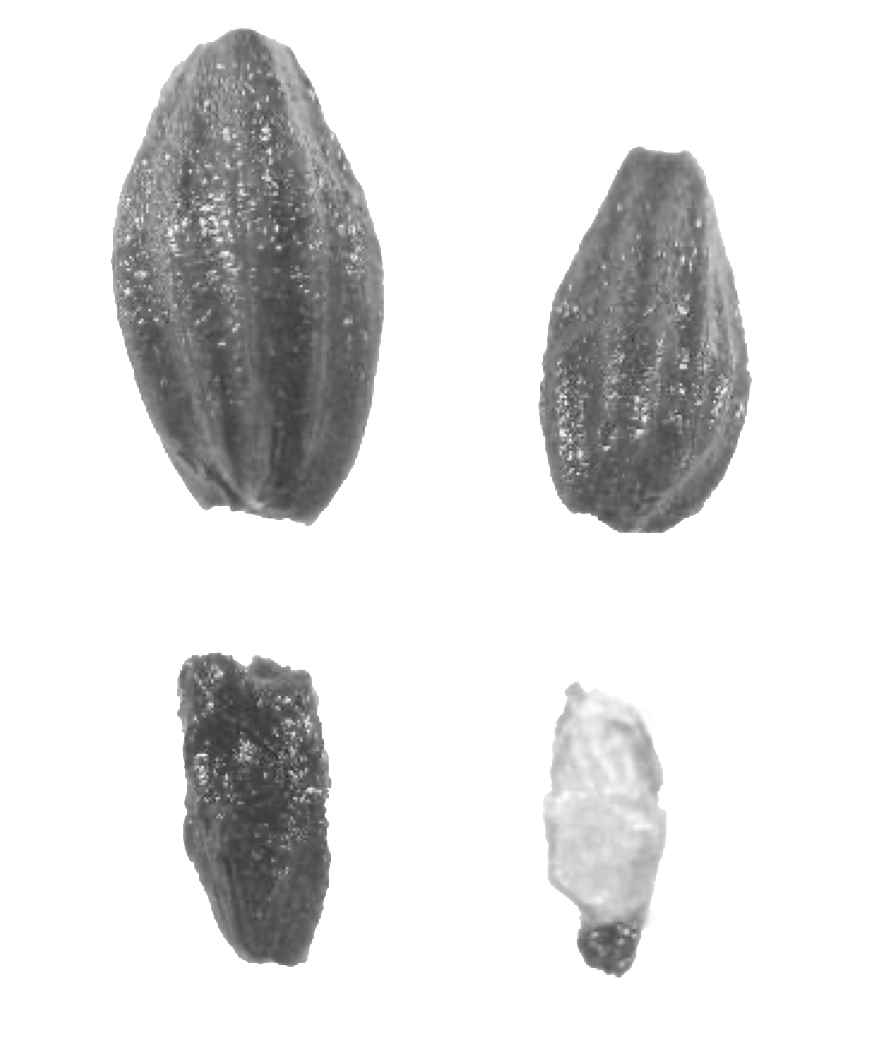

Carbonisation is the most common way of finding seeds when excavating an archaeological site, most notably when using flotation on the samples. Carbonisation occurs when seeds (or other botanical materials) are exposed to fire at not excessively high temperatures and under anaerobic conditions so that the combustion process is not completed. Other factors include the proximity to the fire source, fuel type and elements associated to the seed (i.e. chaff and straw) (Turney et al., 2014, p. 93). Several experiments have been carried out to understand the way in which carbonisation takes place and for a review of the literature on this topic, readers can refer to Pearsall (2015, pp. 41–42). Charred seeds lose their original colour (turning black), but mostly retain their morphology although slightly changing their dimension. The chance of preservation is particularly high considering that charred material is not attacked by bacteria or fungi (Weiss and Kislev, 2007).

Mineralisation is a natural process that leads to the replacement of organic material with inorganic material. Through phosphatisation, soft tissue is replaced by calcium-phosphate minerals that preserve the morphology of the seed (Murphy, 2014). Mineralisation can also occur because some plants are particularly mineral-rich, and the phenomenon takes place prior to deposition. This is known as biomineralisation (Messager et al., 2010). For instance, mineralised seeds can be found in latrines or cesspits (Veen et al., 2013, p. 164).

Organic material maintained in a wet environment under very low oxygen levels (anaerobic conditions) can be preserved as the activity of micro-organism is low or entirely absent. Examples of wet environments include natural ones (lake, riverine, marine sediments, marshes, bogs, etc.) or man-made (pits, latrines, wells, ditches, etc.) (Spriggs, 2014). Waterlogged seeds do not degrade markedly, but their starch, sugar and protein content is low and their colour is dark (Weiss and Kislev, 2007).

This phenomenon is limited to very arid regions (mostly Egypt, some areas of China and Spain), where the complete desiccation of the organic material prevents microbial decay. Where plant material is preserved through drying, the preservation is remarkable; for instance, even aDNA survives in desiccated seeds (Veen, 2018, p. 58).

Plant material can be preserved if found in proximity to metals. Metal oxides when the soil is moist, creating a toxic environment for microbial activity.

The imprints of seeds and plants on the wet clay can help the investigator recognise the morphology of the seed and identify the plant, however the organic material is not preserved and the marks on the pottery are the only visible remains (Schepers and Vries, 2022).

The following map shows the sites under investigation, divided by chronology. Please select the desired chronology (or chronologies) from the legend at the top-right of the map. Every point on the map is clickable to access reference, total seed counts, preservation mode and other details.

R = Roman, LR = Late Roman, EMA = Early Middle Ages, Ma = 11th c. onwardsThe archaeobotanical data available for this project consists in 190 samples with macroremains collected from a total of 120 sites dated between the 1st century BCE to the 11th century CE. The geographical and chronological distribution of the samples varies greatly, with some areas or chronological phases that are better represented in the database. The samples chronological distribution is detailed in Table 3.1 and Figure 3.7.

| Chronology | Northern.Italy | Central.Italy | Southern.Italy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roman | 43 | 5 | 35 |

| Late Roman | 46 | 8 | 10 |

| Early Medieval | 42 | 10 | 17 |

| 11th c. | 12 | 4 | 2 |

Most of the excavations lacked forms of probabilistic or total sampling strategies and instead used visual sampling, which occurs when archaeologists can see or expect to find macroremains in the feature they are excavating. Common features from which samples are collected include pits, hearths, and filled anforae. The pitfalls of this type of sampling have already been outlined in this chapter. In addition to differences in sampling strategies, recovery techniques also differed between reports, which can lead to some taxa being underrepresented. It was not possible to quantify how many sites used flotation or dry sieving, as this information was lacking, especially from older reports. On the other hand, the mode of preservation has been indicated in most cases, with charring being the most common. The list of samples that included the preservation mode in their reports is listed in Table 3.2.

| Preservation | Count |

|---|---|

| Charred | 157 |

| Waterlogged | 26 |

| Mineralised | 47 |

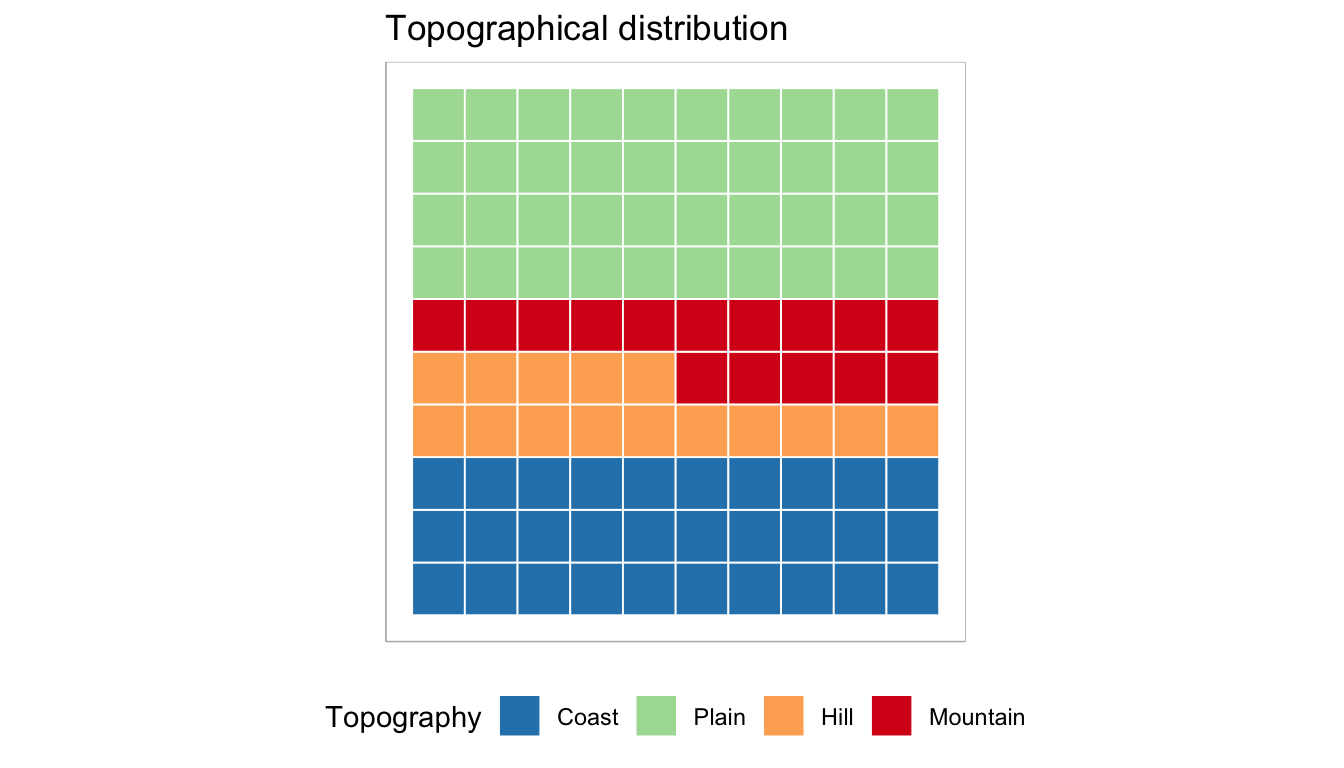

Geographically speaking, the distribution of archaeobotanical samples in the period under investigation exhibits certain patterns within Italy. Specifically, there is a higher representation of samples from northern Italy, indicating a greater focus on archaeological investigations in that region. Conversely, certain areas in the south of Italy show a relatively lower representation of archaeobotanical sampling. Additionally, there is a notable lack of archaeobotanical data from central Italy during the investigated period. These spatial discrepancies in the distribution of archaeobotanical samples suggest varying degrees of research emphasis and archaeological investigations across different regions of Italy. The abundance of samples from northern Italy may be attributed to a combination of factors, such as research interests and more specific factors influencing the preservation and recovery of plant remains in that region. In contrast, the lower representation of archaeobotanical sampling in specific areas of the south and center might indicate a relative scarcity of archaeobotanical investigations or limited attention paid to the study of plant remains in those regions during the studied period. These observations are based on the available archaeobotanical samples and may be influenced by various factors affecting archaeological investigations in different regions. The geographical variability in the number of available samples also concerns the different topographic features, including coasts, plains, hills, and mountains. The topographical distribution of samples can be visually explored in Figure 3.8 and Table 3.3, which indicate that most samples are located at low elevations, either on plains or coasts. This suggests that archaeological investigations and archaeobotanical sampling have primarily focused on these areas. However, a more detailed examination of the relationship between altitude and plant occurrence is provided in the results chapter, where altitude is modeled against the presence of plants.

| Topography | Samples |

|---|---|

| Coast | 54 |

| Hill | 26 |

| Mountain | 26 |

| Plain | 71 |

The botanical species names used in this research adhere to the conventional nomenclature provided by Zohary et al. (2012). In the dataset, the species that were considered were the most common among all excavations, so that plants could be comparable.

Arguably, the most commonly discovered grains in Italian archaeological excavations are free-threshing wheats (Triticum aestivum/durum). They are listed as a single column because distinguishing between hard wheat and bread wheat is challenging without the rachis (Roushannafas et al., 2023). Although notably an important cereal, Triticum spelta has not been included as it was only sporadically recorded. Whenever it was present, it was categorised under the Cerealia und. column, which also comprises other grains belonging to the Triticum group that could not be identified further by the authors. Occurrences of Avena sp. have been recorded whenever found in excavation reports, including the counts of cultivated oats (Avena sativa). This species is challenging to identify as caryopses alone are insufficient, and it is prevalent in Italy as a weed that grows alongside cereal fields. Consequently, although Avena sp. is in the database, limited inferences can be drawn regarding this taxon.

Similar to cereals, the Leguminosae column contains pulses that authors were unable to assign to a species. The Vicia genus is a sizable family of Fabaceae, and some of its members are cultivated. The database lists Vicia faba and Vicia sativa as separate columns due to their frequent occurrence in excavations. Other Vicia types that could not be identified or were only occasionally identified (such as Vicia ervilia) were listed under the Vicia sp. column. The column Lathyrus cicera/sativus (grass pea) contains two species that are difficult to identify below genus level and whose previous identifications have proved unreliable (Tarongi et al., 2023).

A wide variety of fruit species were recorded in the dataset. As with other plants, some counts have been reported in a single column because they were more difficult to identify below genus level, or because they were very sporadic and in danger of being under-represented in the overall quantifications. This is the case, for example, of Prunus sp. The dataset reports separate column for five Prunus species: P. persica (peach), P. domestica (plum), P. cerasus (sour cherry), P. avium (wild cherry), and P. spinosa (blackthorn). Other species that were rare or nuts that could be attributed to a Prunus species were reported in the column Prunus sp. It was not possible in this research to model the occurrence of each fruit species, and models were built for macrocategories as ‘Nuts’, ‘Common domestic fruits’, and ‘Less common fruits’. The latter is comprehensive of mostly wild fruits, berries, and less common domestic fruits: P. cerasus (sour cherry), Cornus mas (cornelian cherry), P. avium (wild cherry), Sambucus nigra (elderberry), P. spinosa (blackthorn), Rubus fruticosus (blackberry), Sorbus sp., and Fragaria vesca (strawberry).