R = Roman, LR = Late Roman, EMA = Early Middle Ages, Ma = 11th c. onwardsThis chapter provides an overview of the zooarchaeological materials used for this research project. Literature review provided an historical overview of the discipline, while this chapter discusses the goals, types, and preservation modes of the remains. In addition to discussing general aspects of the discipline, this chapter also provides a more detailed examination of the specific data available for this research project, which have been stored in the database. The storing procedures are described in Chapter 5.

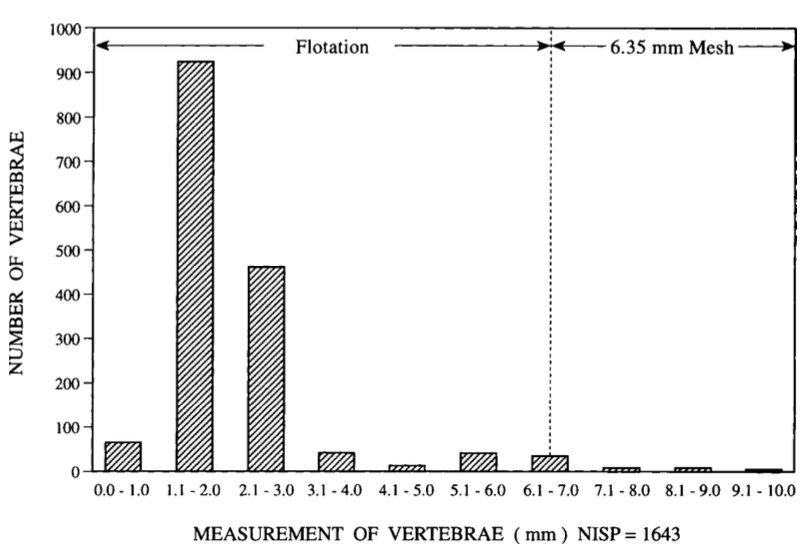

The objective of zooarchaeology is to recover, identify, and document animal remains from excavated archaeological sites to reconstruct the relationship between humans and other animals, as well as farming practices and food patterns. The name of the discipline has been debated since its origins, with the first reference to its practitioners being “zoologico-archaeologists”. Mirroring the anthropological perspective of studying animal remains to gain insights into human behaviour, the discipline is widely referred as “zooarchaeology” especially in the Americas. The term “archaeozoology” is preferred by practitioners who emphasise the biological nature of faunal remains; especially in Africa and Eurasia. Italian scholars refer to the discipline as archeozoologia, reflecting this tradition. More alternatives are also available, including “ethnozoology”, “paleoethnozoology” and “osteoarchaeology” (Clutton-Brock, 2017; Reitz and Wing, 2008, pp. 4–5). Because this thesis deals with humans’ relationship with animals for economic and historical purposes, the term “zooarchaeology” will be used throughout this volume. The importance of archaeology in making inferences about historical environmental questions has already been emphasised in Chapter 3; as with archaeobotany, although textual sources can be useful in answering historical questions, zooarchaeology is essential for verifying and complicating our understanding of the past. Zooarchaeology studies both vertebrate and invertebrate remains. Depending on the research questions, a zooarchaeologist may focus on domestic/wild animals, on a single species, on a specimen (i.e., a single bone) at different scales ranging from a stratigraphic unit to an entire region (Lyman, 1994). The recovery methods for animal bones include in situ examination, screening with sieves, and flotation techniques. All these techniques have already been outlined in Chapter 3. However, it is important to address again the underlying challenges. Visual collection tends to favour larger bones, potentially leading to the loss of smaller finds if not properly sieved. In contrast, flotation proves particularly useful for the recovery of remains such as fish, birds, and mollusca. For instance, fish otoliths, which are structures found in the inner ears of fish, can be challenging to visually identify and are often successfully recovered through flotation. In Figure 4.1, the impact of screening and flotation techniques on the recovery of fish vertebrae from the Kings Bay site, located on the Atlantic coast of Georgia, United States, is illustrated.

Although faunal remains are generally more abundant and easily identifiable compared to botanical remains, the number of recovered remains at a given archaeological site is inevitably influenced by the chosen sampling strategy. As emphasised by Terry O’Connor (2000, pp. 28–30), it is crucial to establish a sampling strategy prior to commencing excavation. The author outlines three potential strategies that can be employed in the field:

As highlighted in the previous chapter, various drawbacks of different sampling strategies have been discussed, including the limitations of blanket, judgemental (or feature-based), and random approaches. These strategies are influenced by factors such as research questions, time constraints, and economic considerations. The blanket approach, which involves collecting all the bone fragments from every context without any selective criteria, may lead to an overwhelming amount of material to analyse. This can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, especially when dealing with large or complex archaeological sites. The judgemental or feature-based approach relies on selecting specific contexts or features for sampling based on prior knowledge or assumptions about their potential significance. While this approach may provide focused data collection, there is a risk of bias and overlooking important information from other contexts or areas of the site. The random approach involves selecting samples in a random or systematic manner to ensure unbiased representation. However, this approach may not effectively capture the full range of variability within the site and may result in missing important data. As the sampling effort increases, the probability of encountering rare species also tends to rise. By collecting a larger quantity of bone fragments or applying a more comprehensive sampling approach, researchers increase their chances of capturing a broader range of faunal remains, including those that may be less common or uncommonly preserved (Reitz and Wing, 2008, p. 110). Ultimately, the choice of a sampling strategy depends on the specific research questions, available resources, and logistical constraints of the excavation project. By considering these factors, researchers can determine the most appropriate approach to ensure the collection of meaningful and representative faunal data within the given constraints.

There are several taphonomic processes that influence the preservation of faunal remains in archaeological contexts. While providing an exhaustive list is beyond the scope of this dissertation, a synthesis presented by O’Connor (2000) offers valuable insights into these processes:

Understanding these taphonomic processes is essential for interpreting faunal remains in archaeological contexts. They provide insights into the complex journey of animal bones from their formation to their recovery and subsequent analysis, shedding light on the potential biases and alterations that may affect the assemblage.

When examining zooarchaeological remains, various methods can be employed to assess the abundance of a specific species at an archaeological site. Two commonly used measures for quantifying abundance are NISP (Number of Identified Specimens) and MNI (Minimum Number of Individuals). Both of them are not without shortcomings, which will be listed below.

The Number of Identified Specimens (NISP) is the measure provided by most reports and is commonly used to estimate the relative frequency of zooarchaeological assemblages. It provides a count of the number of bone fragments identified to bone type and taxon (Lambacher et al., 2016; Orton, 2010). Although being so widely used, NISP is not without its limitations. One key challenge is its sensitivity to bone fragmentation, as it counts every encountered bone fragment, assigning equal weight to each fragment. However, animal bones exhibit distinct patterns of fragmentation, resulting in variations in fragment counts across species. Furthermore, different animals possess diverse types of hard tissue, leading to variations in the ease of identification for different bone elements (Klein and Cruz-Uribe, 1984; Reitz and Wing, 2008). Moreover, the preservation modes of remains play a significant role in the representation of species within the assemblage. Certain species may be better preserved than others due to factors such as differential decay rates or taphonomic biases. Additionally, consumption patterns and butchery practices can influence the preservation of specific bones. For instance, if an animal was butchered outside the settlement and only selected meat portions were brought in, certain bones may be underrepresented in the assemblage (Kent, 1993). Excavation methods, such as sieving and flotation, can introduce biases by selectively recovering smaller and more fragile remains like fish vertebrae, mollusc shells, or small mammal bones. Consequently, the application (or lack thereof) of sieving and flotation can introduce biases in the composition of the assemblage. In addition to these challenges, another issue that can inflate NISP counts is the inclusion of an entire skeleton of an animal. This can skew the relative frequency estimates, as a single individual contributes a disproportionate number of bones to the assemblage. To address this concern, another measure called the Minimum Number of Individuals (MNI) is often used (O’Connor, 2000, p. 56). Considering these factors, the NISP measure should be interpreted with caution, taking into account the complexities associated with bone fragmentation, preservation biases, consumption practices, and excavation methods.

Introduced by Theodore White (1953), the Minimum Number of Individuals (MNI) is a measure that estimates the minimum number of individuals needed to account for all the skeletal elements of a particular species found at a site. MNI takes into account the duplication of skeletal elements within a species, providing a more refined assessment of the faunal assemblage. Analysts determine MNI by examining the bones recovered and identifying the minimum number of individuals required to account for each bone element, considering factors such as articulation, overlap, and symmetry. Despite its utility, MNI has faced criticism from archaeologists, leading to the development of alternative approaches for its refinement. Sándor Bökönyi (1971, 1970) and Raymond Chaplin (1971) proposed incorporating additional factors like age, sex, and size to improve the accuracy of MNI calculations. In contrast, Donald Grayson (1981; Grayson and Dimbleby, 2014) highlighted the close relationship between MNI and NISP, emphasizing also how sample size affect the MNI estimation. A known limitation of MNI is its potential to overestimate the presence of rare taxa within an assemblage. This occurs because a single specimen of a rare taxon is given the same weight (i.e., a count of one) as multiple bones from a more common taxon (O’Connor, 2000, p. 60). Furthermore, Cornelis and Ina Plug and Plug (1990) cautioned against using MNI for further numerical analysis, including its conversion to relative frequencies, due to the mathematical incoherence of proportions derived from minimum values. While MNI has been subject to ongoing debate and critique among zooarchaeologists, with some stating that ‘critiquing MNI might be considered a growth industry among zooarchaeologists’ (Reitz and Wing, 2008, p. 206), this research primarily relies on NISP as the primary data measure. NISP is commonly reported in zooarchaeological studies, and its estimation methods tend to be less variable compared to MNI. While acknowledging the ongoing discussions surrounding MNI, this research opts to utilize NISP due to its widespread availability and more consistent application in reporting zooarchaeological data.

R = Roman, LR = Late Roman, EMA = Early Middle Ages, Ma = 11th c. onwardsThe zooarchaeological data available for this project consists in 465 samples with faunal remains collected from a total of 228 sites dated between the 1st century BCE to the 11th century CE (Figure 4.2). The geographical and chronological distribution of the samples varies greatly, with some areas or chronological phases that are better represented in the database. The number of samples for each phase is detailed in Table 4.1, with samples that span more chronologies repeated. As explained in the methods section, some samples were dated between two chronologies, and the entry had to be repeated twice. Table 4.2 reports the total NISP count of the samples in the database, with and without the repetition. Table 4.3 shows instead the NISP count of samples divided by chronology. The group sizes in the dataset do not present significant class imbalance issues, particularly for the Roman, Late Roman, and Early Medieval phases. However, the 11th century phase has the smallest group size. This smaller size can be attributed to the fact that it represents the upper boundary of the research period under investigation. From what concerns spatial dispersion, there is no discernible geographical pattern in the distribution of zooarchaeological samples, although certain regions lack a substantial amount of data. Notably, central Italian regions such as Umbria and Marche are among those with limited representation in the dataset. In contrast, there is a concentration of samples specifically related to the Roman and Late Roman chronologies in the city of Rome and Ostia. The uneven distribution of samples in different regions and the concentrated presence of samples in Rome and Ostia are addressed separately in the results section. This section includes an analysis of the effect of Rome on the urban statistical models, examining how the abundance of samples from these locations may impact the overall findings and interpretations.

| Chronology | n |

|---|---|

| Roman | 191 |

| Late Roman | 204 |

| Early Medieval | 154 |

| 11th c. | 69 |

| Total NISP | Total NISP of pigs/cattle/sheep/goats | |

|---|---|---|

| Unique_Samples | 264962 | 223686 |

| Repeated_Samples | 360891 | 304086 |

| Chronology | Total NISP | Total NISP of pigs/cattle/sheep/goats |

|---|---|---|

| Roman | 84384 | 73806 |

| Late Roman | 117613 | 98551 |

| Early Medieval | 115680 | 96868 |

| 11th c. | 43214 | 34861 |

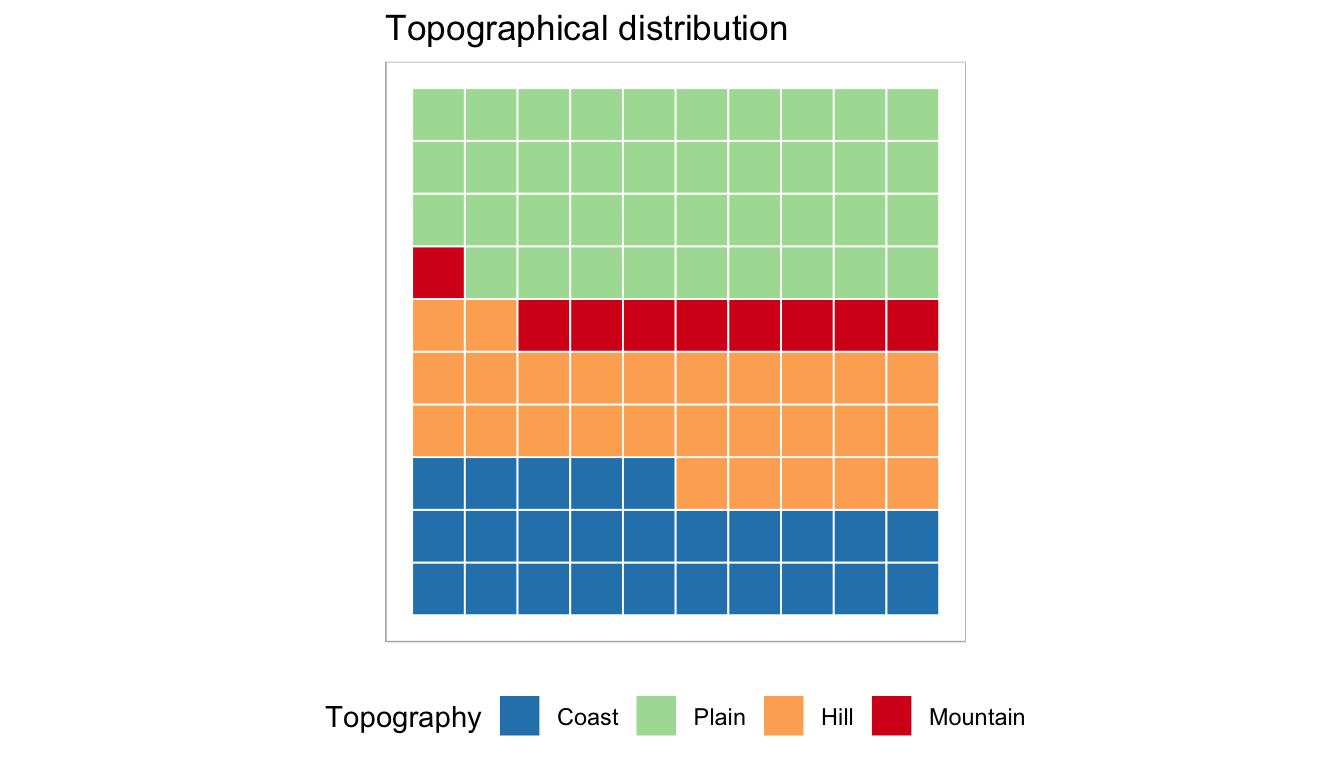

In contrast, there is noticeable topographical variability in the areas that have been sampled. The distribution of samples demonstrates that plains and coasts exhibit a higher number of samples, with 181 and 119 samples, respectively. On the other hand, hills (n = 125) and mountains (n = 40) are slightly less represented in comparison. However, in addition to topographical models, the analysis also incorporates models that consider the elevations of the sites. This approach allows for a more detailed examination of the relationship between animals occurrence and site elevations. The results section provides a breakdown of the sites categorised by their elevation, providing further insights into the influence of elevation on the distribution of zooarchaeological remains.

The names of the faunal species used in this study adhere to the conventional Linnean nomenclature provided in Gentry et al. (2004). To ensure comparability, the dataset encompasses most of the common species encountered in excavations. Specific models have been developed for the primary domesticated species - Sus scrofa (pigs), Bos taurus (cattle), Ovis aries (sheep), and Capra hircus (goats). Sheep and goats are difficult to distinguish unless specific bones (or the whole skeleton) are found in archaeological excavations, and are therefore modelled together (Halstead et al., 2002; Prummel and Frisch, 1986; Zeder and Lapham, 2010). In the analyses, these animals are collectively referred to taxonomically as caprine, aligning with the nomenclature used in other studies (Albarella, 2019; MacKinnon, 2002; Salvadori, 2019; Trentacoste et al., 2023; Trentacoste et al., 2018).

For statistical analyses of rarer species, these have been grouped as follows:

Other species included in the database but not modeled due to their rarity, inedibility, lack of economic significance, or uncertain identification include Canis familiaris (dog), Equus asinus (donkey), Equus caballus (horse), Ursus arctos (bear), Vulpes vulpes (fox), and others. As previously discussed, fish and birds are notably underrepresented in excavation reports. Molluscs, often not recorded or not differentiated between terrestrial and marine species in older excavations, are more specifically identified in recent excavations. These instances have typically been documented in the extra_notes column with their total count in the mollusca column.